Media Release 10 January 2020

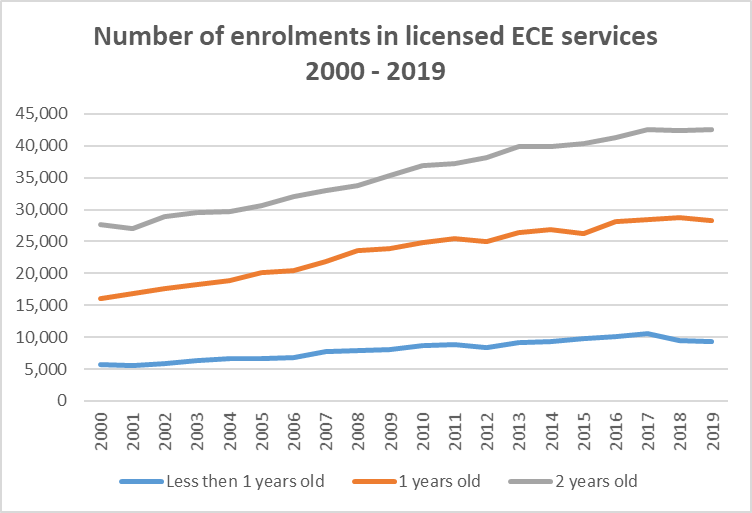

Family First says that government statistics reveal that there continues to be a significant increase in the numbers of babies and toddlers in childcare, and the length of time they are spending there, with some babies and toddlers in daycare almost as long as a parent in fulltime work, yet the government is ignoring the real concerns of whether this is good for very young children and babies.

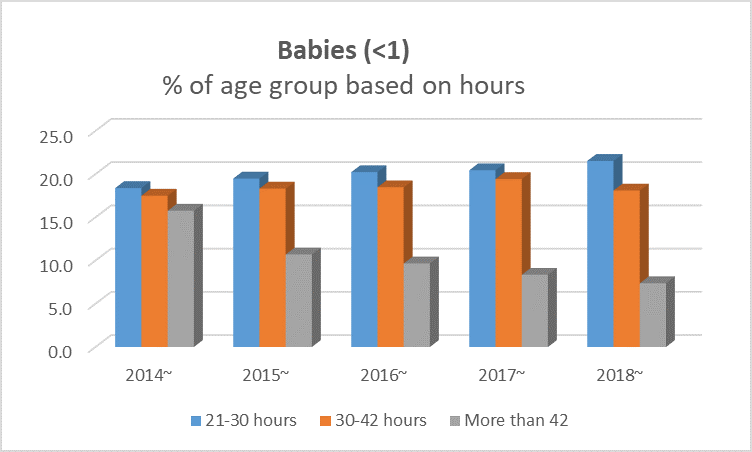

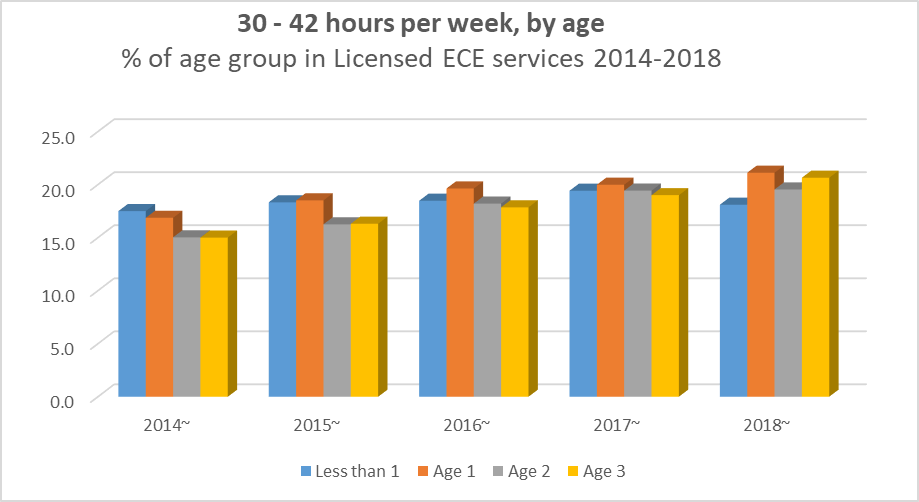

According to the data, of the 135,000 children in a licensed ECE service, more than a quarter of the children under the age of one are in daycare for longer than 30 hours per week, and a further 21.5% between 21-30 hours per week. 7.4% are there longer than 42 hours each week – longer than a 40-hour adult working week. For one year olds, more than 30% attend longer than 30 hours per week with almost 10% attending over 42 hours each week. There has also been a 30% increase in the last 4 years in the number of two year olds attending between 30 – 42 hours.

However, there has been an overall welcome decrease in the number of young children attending longer than 42 hours per week – although this may be more to do with the cost factor.

Of most concern is the proportion of babies and toddlers in very long periods of childcare (42 hours-plus) being higher than rates for 3 and 4 year olds.

“These statistics are concerning. Some babies and toddlers are spending more time in daycare than primary age children are expected to spend at school when they first start,” says Bob McCoskrie, National Director of Family First NZ.

“With government spending on early childhood education being almost $1.9b per annum, it is essential that the benefits of the investment in ECE are weighed against the real needs of very young children & babies and their families.”

The report “WHO CARES?: Mothers, Daycare and Child Wellbeing in New Zealand” argues that attending daycare for an extended time and the consequent separation from parents is a significant source of stress for many young children which could have potential long-term consequences for their mental and physical health as adults.

The report warns that daycare continues to be evaluated by later child outcomes in terms of ‘skills’ such as language or ‘school readiness’. But what has proved elusive is an understanding of how the young child is affected emotionally and physiologically, and how they experience daycare while they are actually there. Babies can’t speak and toddlers have limited verbal abilities. However, a new generation of research from the biosciences is starting to provide an insight into the real-time effects of daycare. These findings are at odds with the information most policymakers and members of the public have been exposed to. Moreover, there is no mention of this evidence by either the Ministry of Education or the Education Review Office (ERO), which regularly monitors New Zealand’s childcare centres.

The Brainwave Trust’s report “Childcare: How are the Children Doing?” states; “Although the evidence suggests that some high quality childcare may benefit children over 3 in certain circumstances, this does not mean that starting earlier and attending for longer hours is also beneficial. In fact, our research indicates that there may be risks involved with non-parental care “too early” and “for too long each day”.

“There is growing evidence of profound beneficial neurobiological effects a mother’s physical presence has on her young child that cannot be achieved by anyone else including paid childcare workers. Mothers have been undervalued, and many parents use daycare because they simply can’t afford not to,” says Mr McCoskrie.

“Our babies and toddlers are being used in a massive social experiment and policymakers are too scared to ask the hard questions around whether this is in the best interests of both the child and the family.”

“Full-time parenting should be seen as a child’s right, and any discussion of daycare should cease communicating what is in the interests and convenience of adults, and instead make judgments about what is likely to be in children’s best interests. New Zealand should also undergo a timely and long overdue re-evaluation of motherhood,” says Mr McCoskrie.

“The political and policy focus has been on the needs of the economy and the demands on working mothers, rather than on the welfare of children and the vital role of parents.”

ENDS