Olivia Boyd is our teenage guest writer who is very passionate about supporting the pro-life movement and ending human trafficking. Upon completion of her High School education, she intends to study law and psychology. She has an interest in human rights and social psychology, and is an active member of the PragerForce group for students and young professionals. Olivia will be contributing articles to Family First this year as part of her Duke of Edinburgh award.

Please read Olivia’s article on the unintended consequences of legalising assisted dying…

Legalised in New Zealand by the End of Life Choice Act 2019, assisted dying is the term that includes both euthanasia and assisted suicide. Someone may seek assisted dying in New Zealand if they are at least 18 years old, terminally ill, and have been given up to six months to live. Legalising this has been justified by its supporters as a human right. However, there are many issues with legalising assisted dying and there may be unintended negative consequences. It sends harmful messages to society’s most vulnerable members, and it also causes a slippery slope towards widening the eligibility criteria.

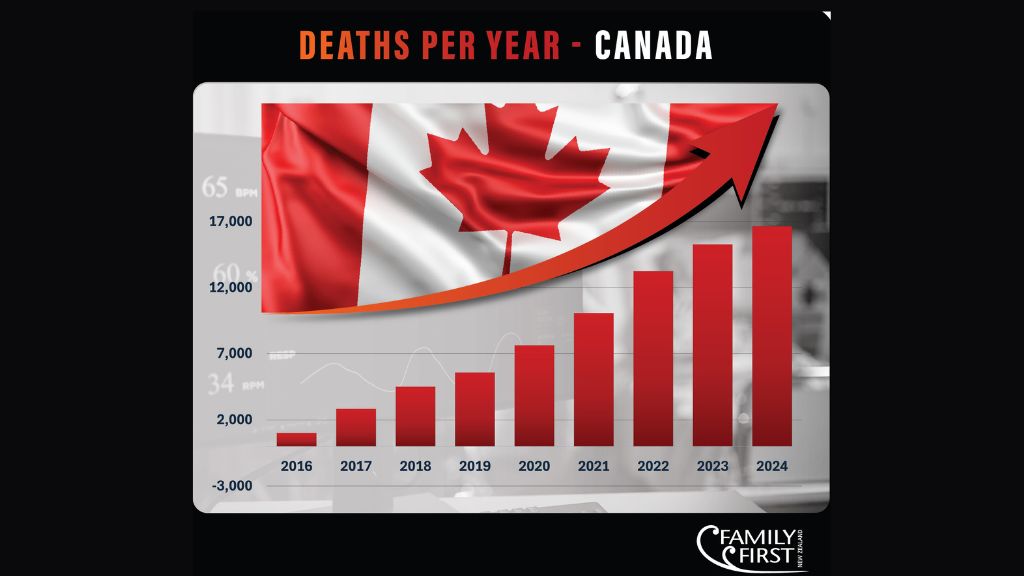

Legalising assisted dying for a specific group of people and calling it a human right will inevitably lead to the eligibility criteria being widened. We can see examples of this overseas in places that have legalised assisted dying before New Zealand. In Belgium the age requirement has been removed so that children as young as nine years old have now accessed assisted dying. In 2013 in the Flanders region of Belgium, 1.7% of people who were euthanized had this happen involuntarily. In the Netherlands parents can decide to euthanize their less-than-one-year-old infant, and children one year old and older can decide to be euthanized with parental consent. There were also 166 people with dementia who were euthanized involuntarily in 2017, and they are in the process of legalising assisted dying for elderly people over 70 who are “tired of life.” (1) In 2021, 3.3% of all deaths in Canada were from MAID (Medical Assistance In Dying).(2) Canada is trying to legalise MAID for the elderly, children, and those with a mental illness. All three of these countries legalised assisted dying years before New Zealand did, and they paint a picture of what our future may look like.

Legalising assisted dying for elderly people will send the message to our elderly population that they are a burden on us and that it would just be better if they died to ease that burden on their loved ones. Sadly, some family members may influence or coerce their elderly family member to seek assisted dying because they don’t want their inheritance to be spent on caring for the elderly family member. An elderly person may decide that they shouldn’t burden their descendants financially or emotionally anymore. It also encourages elder abuse, which is already a problem in New Zealand—one in ten people experience it. (3) One New Zealand nurse shared, “I have found myself comforting many elderly patients who, through heaving sobs, recount their belief that they are a burden on their families, that they’d be better off dead, that they are cutting into their family’s inheritance, or they are of no more use to anyone.” (4) Instead of letting our elderly population feel as if they are too burdensome on us and that they should just die prematurely instead of naturally, we need to provide the highest possible quality care for them and clearly send the message that they are not a burden. If we invest resources, time, and ourselves into this important sector, we are demonstrating that we value our elderly.

Legalising assisted dying for disabled people will send the message to those who are disabled that their life does not have the same value as others. Since it was already legal in New Zealand to refuse medical treatment, those being kept alive by medication may be eligible for assisted dying if they stop treatment. As Dr John Fox, who suffers from spastic hemiplegia, said, “Don’t tempt us to end our lives.” (5) People with disabilities may feel burdensome on their loved ones, they may not want to endure more pain, and they may feel that their life does not have much of a purpose because they are not able to do some things. However, their lives have just as much value as anyone else’s. If a person was to prematurely end their life, we would never know what the impact of their life might have been or if their circumstances might have changed for the better. Another thing to consider is, legalising assisted dying for disabled people may also create a system where the choice to die may not be a choice at all, because access to adequate care may not be as easily available as the option for assisted dying.

Legalising assisted dying sends the message to our society that sometimes the best thing to do is to give up, which could be deadly for those already struggling with their mental health. New Zealand already has the highest youth suicide rate in the world, and legalising assisted dying will only increase this number of lives lost. A significant shift in our cultural thinking is possible when a list of reasons to die are laid out in the law thus validating the decision someone may make to commit suicide. It sends mixed messages on suicide and undermines the work of suicide prevention. People suffering from mental health and depression may become more likely to commit suicide because of this confusing messaging.

If we don’t continue to speak up on the potential consequences of this legislation, it’s highly likely that the eligibility criteria for assisted suicide will widen as it has overseas. Our culture may end up accepting assisted dying as a viable option for ending one’s life—potentially for any reason, at any age, and in any circumstances. We have to ask ourselves: is this really the future we want, where life is no longer sacred and worth defending? If we really want to lay the groundwork for a society where all life is valued, it starts in the womb and continues to the end of life itself. Let’s not relent on speaking up and defending life.

(1) www.voiceforlife.org.nz/euthanasia and www.defendnz.co.nz/what-does-international-evidence-show-us

(3) www.defendnz.co.nz/are-there-risks-to-the-elderly

(4) www.thinkingmatters.org.nz/2020/07/thinking-critically-about-euthanasia/

(5) familyfirst.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Euthanasia-Fact-Sheet.pdf